Bernard Mandeville

1670-1733

'S WERELDS EERSTE MODERNE PSYCHIATER

News blog on Mandeville

The website www.bernard-mandeville.nl was launched April 2, 2005, the tercentenary of The Grumbling Hive, or Knaves turn’d Honest. It is a part of the project to make the works of Bernard Mandeville accessible to speakers and readers of Dutch. This website being a work in progress, it is often being amended, extended and, hopefully, improved.This blog presents news items which may be interesting to foreign students of Bernard Mandeville as well.

Recent news items on Bernard Mandeville

• Mandeville's surname.

The name of Mandeville is etymologically of Saxon origin, consists of the word “mande”, meaning common and “wiler”, meaning hamlet. Mande or Mante may also be understood as personal names. Anyhow, Mandeville or Manteville is a French corruption of the place-name “Man(t)(d)ewiler”.

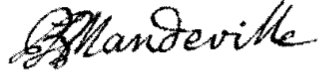

• Mandeville's signature: BDMandeville. D stands for 'de' in French, meaning 'from' or 'of'.

• Bernard Mandeville's descent.

Mandeville is a (5th generation) descendant of a military man called Jan or Joannes from Mandville, a small region now at the Belgian-French border, and his Frisian wife Anna Tyepcke. See the page 'Mandeville in the Netherlands, from South to North.' Herein also some modifications of earlier findings, published in Arne C. Jansen, Bernard Mandeville, some recent genealogical discoveries , in Notes & Queries Advance Access 2009 http://nq.oxfordjournals.org/ on May 7 2009.

• Anna Tiepcke.

The mother of the first Dutch Mandeville boys Michael, Bernardus and Nicolaas, born at Leeuwarden, so Bernard Mandeville's great-great-grandmother, was called Anna Tyepcke (pron. Tjepke). See the page Mandeville in the Netherlands, from South to North .

• Birth.

On July 12, 2007, we announced Bernard Mandeville’s date and even time of birth: Bernard Mandeville was born on November 15, 1670, at about three o’clock in the morning. The page Biografie shows a picture of a note by his father Michael de Mandeville, written in the Mandeville family bible (in private Dutch ownership), stating this day and hour of birth of his son Bernardus. Bernard was born at Rotterdam. However, on Thursday November 20, 1670, his baptismal name became Barent, after his grandfather Barent Verhaer, as shown by a photocopy of the register of baptisms of Rotterdam. While in England, Mandeville kept his Dutch nationality.

• Mother and sister.

Bernard Mandeville’s mother Judith Verhaar (1642-1688) was born on December 22, 1642, at Schoonhoven, where she grew up. She died on March 29, 1688, at Rotterdam. She gave birth to five children, of whom three died as babies. Bernard was her third child. His sister Petronella Clementia (1684-1774), was further brought up by her aunt Elizabeth de Mandeville at Arnhem. Their aunt-and-niece relationship may have been the model for The Virgin Unmasked (1709). Petronella married in 1709 Jan van Laer from Zwolle.

• Maternal grandmother.

The name of Bernard Mandeville’s maternal grandmother and Barent Verhaar’s wife is Meinsje Jans Hamsarda. Hamsarda, as she wrote herself, means ‘from Hamsard’, i.e. being born in a village by the name “Hamseerden”, as the clerk put it, now Hamswehrum near Emden. Her father was Jan Atis, probably a captain or skipper from the seaport of Stavoren, in Friesland, where she lived when marrying Barent Verhaar in 1639. Meinsje (short for Clementia) Hamsarda was born in 1620.

• Barent Verhaar.

Mandeville’s maternal grandfather Barent Verhaar, was born at the Hanseatic and fortified town of Zaltbommel, and christened Bernt there on April 4, 1609.

• Further kinship.

Through Barent Verhaar, Bernard Mandeville was related to well-known Geneva-Italian families originating from Lucca, such as the Diodatis, Burlamacchis etc. and also to the Le Clercs. For more information, see Mensen spreken niet om begrepen te worden (2007), note 165.

• Mandeville’s wife.

Elizabeth (Joyce) Lawrence (or Laurence) (1674-1732). Her name was not Ruth Elizabeth, as mentioned by F.B. Kaye, I, p. xx. The mistake has been caused by a misreading of Mandeville’s marriage licence allegation dated 28 January 1699. Elizabeth was most probably born 29 November 1674, parish of St Giles Cripplegate, London, daughter of John Lawrence and Ann Lawrence.

• Death of Mandeville’s wife.

Elizabeth died in 1732, and was buried at St Giles, Camberwell, on April 25, 1732. This fact was presented by mrs. Lyndesay Williams, who is in genealogical research on the English Mandevilles.

• ‘Out of town’.

After having lived in London, Mandeville and his family escaped to the country, which was then south of the Thames. At least since 1706 Bernard Mandeville lived with his family in Long Walk, Bermondsey, in the parish of St Mary Magdalen (source: mrs. Gill Edgell). Later he moved to the parish of St Mary, Lambeth, more precisely it seems at Kennington (Lane), till very shortly before his death.

• Burial of Mandeville.

Mandeville died at Hackney on January 21, 1733 (Old Style), but according to a burial entry of St Giles, Camberwell, he was buried in the churchyard of Camberwell on January 25, 1733. Source: mrs. Lyndesay Williams.

• Jazz club.

The Crypt is a decent jazz club and is aptly named based as it is in a 300-year-old basement of St Giles church in Camberwell. Bernard Mandeville was there. The remains of the members of his family have been carried away into this crypt, where behind a wall there are two small rooms to the side with no doors and a table in each. In these rooms the bodies must have lain for ‘a short carry away’ until the Mandeville Tomb in St Giles churchyard had been prepared for the burial. And in 1733 Bernard Mandeville himself was carried away into this crypt. The churchyard being turned into a park, The Crypt is suitably reminding us of Bernard Mandeville’s analysis of any society and any group as being 'jazzy', due to men’s self-liking.

• Mandeville's Portrait.

Because of the sitter’s resemblance to the two images of Mandeville on this website (see page Portrait of Bernard Mandeville), his age, and our impression of the sitter’s character, we have submitted our idea to the NPG, that the unknown person on a portrait at NPG might be Bernard Mandeville. (N.B. The portrait on Wikipedia, article ‘Bernard Mandeville’, is false: it portrays Jean Jacques Rousseau.)

• Bernard Mandeville’s children.

In 1733, Bernard Mandeville and his wife Elizabeth had two (surviving) children, Michael (1699-1769), and Penelope (1706-1748). See below. But baptismal entries of St Giles, Cripplegate, and burial entries of St Giles, Camberwell, show that Mandeville, while living in England, became the father of (at least) 3 more children, a fact so far unknown. These three children all died at a young age. Their names are Petronella Clementia, Clementia and Elizabeth. More information about them: 1) A girl, Petronella Clementia, born July 16, 1701, whose mother was Elizabeth, and who was named after Bernard Mandeville’s sister Petronella Clementia (1684-1774). This daughter was buried on May 6, 1702. 2) A girl, Clementia, named after Mandeville’s maternal grandmother Meinsje (Clementia) Hamsarda. Her mother was Elizabeth. She was buried in the churchyard of St Giles, Camberwell on February 28, 1709.3) A girl, Elizabeth, whose mother was Elizabeth as well. She was baptised on 24 December 1708 at St Mary Magdalen, Bermondsey (source: mrs. Gill Edgell) and buried on April 25, 1709, at St Giles’ Churchyard, Camberwell. Source: mrs. Lyndesay Williams.

• No illegitimate child.

On May 4, 1700, Mandeville, living in the parish of St. Giles Cripplegate “within the Freedom” in Londen, became the father of a son called John, named after his maternal grandfather John Lawrence. His mother's name in the register was Joyce, which was the second name or usual name of Mandeville's wife Elizabeth. He was baptised on 16 May 1700 and buried on 13 Augustus 1702, also at Camberwell.

• Penelope Mandeville

Mandeville's daughter Penelope was born on 24 August 1706 and baptised on 19 September 1706 at St Mary Magdalen at Bermondsey (source: mrs. Gill Edgell). She married John Bradnox, a weaver, in London, on April 14, 1726; both licensed St. Mary’s parish, Lambeth. John was born on 2 November 1706. In 1726 John’s mother was Martha Lawrence, wife of William Lawrence, both of Lambeth; she was the widow of Paul Bradnox, of the parish of St Olave, Southwark.

• John Bradnox and Penelope Mandeville.

This couple lived at Lambeth, and became the parents of 5 children: John (1727-1737), named after his paternal grandfather: John Bradnox; Bernard (1728), named after his maternal grandfather: Bernard Mandeville; Elizabeth (1734), named after her maternal grandmother Elizabeth (Lawrence) Mandeville; the twins Penelope and Judith (1739), of whom Judith was named after her maternal greatgrandmother Judith Verhaer; and Ann (1741).

• Penelope's inheritance.

‘To Penelope my Daughter I bequeath twenty Shillings for a Ring’. Mandeville wrote this in his will on April 28, 1729. Penelope was a married woman then, which explains her share in the right of inheritance at the time.

• John Bradnox's death.

John Bradnox died on January 1, 1741, shortly before his daughter Ann‘s birth. He was buried at St Mary Newington, a parish next to Lambeth.

• Penelope Bradnox - Mandeville

Penelope passed away in 1748. Then there were two surviving children, Elizabeth and Ann.

• Michael Mandeville.

Penelope’s brother Michael, living at Kennington (also indicated as Kennington Lane) in the parish of Lambeth, died without issue. In 1741 he became the guardian of his sister Penelope’s two surviving children Elizabeth Bradnox and Ann Bradnox. These children are not mentioned in Michael Mandeville’s will (1766) and so far, it is unknown what happened to them. In this will, Michael Mandeville does mention ‘my kinswoman Ann Dunston, wife of Edward Dunston, of Tring, in Hertfordshire’. ‘Ann Dunston’ was Ann Robinson, of Chesham, who married Edward Dunston of Tring, where he was an inn keeper, at Little Gaddesden on 5 January 1735; she possibly was a maternal cousin.

• Bernard Mandeville’s background

Mandeville's background is the typical mainstream Dutch context, that is being a “poorter”, an exponent of the “portspeople”, inhabitants of an amazingly large and dense number of port towns and their immediate surroundings in The Netherlands, a decentralised civilization, free from of any feudalistic powers (church, nobility). Therefore the portspeople are self-conscious, neither courtly nor slavish. They are no “burghers”, such as people in neighbouring countries chiefly are, who tend to value themselves and others in relation to positions of authority. Mandeville may be situated in the tradition of Erasmus, Coornhert (1522-1590), the eminent exponent of Dutch mainstream culture - including its typical political and religious (‘Remonstrant’) notions (see Gerrit Voogt, Constraint on Trial: Dirck Volkertsz Coornhert and religious freedom (2000), and Hugo de Groot (Grotius).

• No Illustrious School.

After the Latin or Erasmian School at Rotterdam, Mandeville went straight to the Leiden University. This was the usual way for Dutch students. It was intended that students at the university began their education in the artes or philosophy faculty. For a long time, the artes was considered a continuation of the Latin school. This faculty was intended as preparation for a study in the three other and higher disciplines (law, medicine , theology). So it should be noted that Mandeville did not attend the so-called ‘Illustrious School’ at Rotterdam (which, by the way, was a vague and short-lived Calvinistic undertaking, with extemely few pupils, and avoided by the Arminians or Remonstrants).

• Dutch ‘portspeople’ compared with ‘burghers’.

Bernard Mandeville was quite aware of national and cultural differences. In The Virgin Unmasked , pp 162 ff. (“In Holland there is no difference between the sovereign and the beggar.”) he described the Dutch as being saucy. His own sauciness corresponds with the mainstream of Dutch culture, which may be called exceptional compared to the mentalities of surrounding nations. The saucy (direct or “boorish”) behaviour of portspeople has always been criticized by “burghers”. Their politeness is urbanity, not courtesy or courteousness. Already in the 16th century, more than half of the Dutch population lived in towns, and their towns equal ports. On the other hand, this very exceptionality of Dutch culture, having originated from pre-medieval times, has always been attractive to foreigners and will be future-proof in a world of closely connected modern cities and towns; more than half of the world population being urban now.

• Some Dutch influences.

In Bernard Mandeville's poems some specific Dutch influences (Rabus, Van Focquenbroch) are evident. See Research items.

• Early Dutch reception of Mandeville’s Grumbling Hive or Knaves turn’d Honest .

When the Amsterdam merchant and poet Jan de Regt (1665-1715) wrote his most famous poem called Slechten Tyd (‘Wicked Time’) in 1709, he had got most likely his inspiration from Bernard Mandeville’s Grumbling Hive or Knaves turn’d Honest (1705). Its title Slechten Tyd (‘Wicked Time’) may have been derived from Mandeville’s Typhon (1704), p. 5 and 6, the lines: ‘An Age, that spoil’d by Peace and Plenty […] I say ‘twas in that wicked time’. Writing in line with The Grumbling Hive was also Dirk Santvoort (1653-1715), in his Zedig Ondersoek ('Moral Inquiry') (1709).

• Two poems by Mandeville, written in Dutch.

These items nr 16 and 17 in his Bibliography, called Versoek-schrift and Dankzegginge , were discovered on November 9, 2004. Published on this website and in Nieuw Letterkundig Magazijn , Jaargang 23 (2005).

• Edward Ward.

For Versoek-schrift , the first of these two poems in Dutch, Mandeville made use of Edward Ward’s (1667-1731), The Author's Lamentation in Time of Adversity , included in The Poet’s Ramble after Riches.

• Cornelius Pieter Schrevelius.

Talking about A sermon preached at Colchester, by the Reverend C. Schrevelius ( 1708), Edward Hundert ( The Enlightenment’s Fable , 1994, p. 23, note 10) writes: “Schrevelius was a classicist who published no other sermons. This work is likely a satiric performance by Mandeville himself.” Hundert is wrong: the Colchester minister was a different Schrevelius, namely Cornelius Pieter Schrevelius (1682-1716). He was a Dutch clergyman, raised in a Remonstrant family by the name Geselle. More information about Schrevelius on the page Preek in Colchester.

• Philopirio.

Edward Hundert ( The Enlightenment’s Fable , 1994, p. 42) misspells the name Philopirio, being one of Mandeville’s characters in his Treatise of Hypochondriack and Hysterick Passions (1711) or - Diseases (1730), as Philiporo. If not a misreading or misspelling, but a ‘rectification’, Hundert would have explained it in a footnote. Anyway, there’s nothing amiss with Philopirio.

• Galileo Galilei.

In his Preface to The Fable of the Bees, Part II , Mandeville made a mistake. He mentions Gassendus, but he refers to Galileo Galilei, viz. Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo (1632). More on this subject, see Mensen spreken niet om begrepen te worden (2007), note 46. See also Mario Relich, The Technique of Philosophical Dialogue in the Works of Mandeville, Shaftesbury and Berkeley (1976, unpubl. diss.), p. 151, n. 2.

• Annotation of The Grumbling Hive, or Knaves turn’d Honest.

An elaborate annotation in Dutch, relating Mandevilles poem to its main sources, can be found in De fabel van de bijen (2008). These sources are: 1) White Kennett’s sermon Christian Honesty Recommended (1704); 2) François (de Salignac de La Mothe) Fénelon’s (1651-1715), Les Avantures de Télémaque (The adventures of Telemachus); 3) Johan van Beverwijck, Joost van den Vondel and Chavigny de la Bretonnière (see below).

• 'The Spaniard’s own Confession’.

Mentioned by Mandeville in The Fable of the Bees , Remark Q, ed. Kaye, p. 195, and in Free Thoughts. Not solved by Kaye, see his note p. 195-6. Who or what is meant? Mandeville is referring to the famous work by Bartolomé de las Casas (1484-1566), Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias (1552), which was translated as The Tears of the Indians: Being an historical and true account of the cruel massacres and slaughters of above twenty millions of innocent people; committed by the Spaniards (1656). More on this subject: see De fabel van de bijen (2008), note 223. Information about Bartolomé de las Casas and this book is available on the internet.

• Mandeville and Darwin.

Stephen G. Alter, Mandeville’s Ship: Theistic Design and Philosophical History in Charles Darwin’s Vision of Natural Selection (Journal of the History of Ideas - Volume 69, Number 3, July 2008, pp. 441-465) proves Mandeville’s direct influence on Darwin.

• Horatio’s identity.

In the dialogues of both The Fable of the Bees, Part II, and The Origin of Honour etc, Cleomenes (Mandeville's alter ego) is discussing with a friend called Horatio. Horatio, who also figures in Artesia's essay in The Female Tatler nr 109 , is most likely Henry St John, viscount Bolingbroke (1678-1751). The design of The Fable of the Bees, Part II seems to be derived from the story of Atticus, Antonio and Fulvia.

• ‘Physician of the soul’.

Mandeville’s designation of Christ as ‘physician of the soul’ (Matt. 9:12; Marc. 2:17; Luc. 5:31) in The Origin of Honour and the Usefulness of Christianity in War (1732), p. 205, may have been influenced by Hendrik Laurensz. Spiegel's term 'zielenarts', i.e. 'soul-physician', in his Hertspieghel (mentioned before), line I. 136.

• Alfred Owen Aldridge’s mistake.

Aldridge tells in Franklin’s “Shaftesburian” dialogues not Franklin’s (in American Literature, Vol. 21, No. 2 (May, 1949), pp. 151-159), p. 151, that the Horatio in these dialogues is “a hedonist, egoist, and relativist, and loosely a spokesman for the philosophy of Bernard Mandeville”. However, this is a mistake: Cleomenes is the spokesman of Mandeville’s opinions in The Fable of the Bees, Part II (published early in 1729), and not Horatio. The two dialogues between Philocles and Horatio concerning Virtue and Pleasure - formerly wrongly ascribed to Benjamin Franklin -, appeared in Robert Walpole’s London Journal no. 504, March 29, 1729 and no. 529, September 20, 1729, and were written by “Publicola” (i.e. James Pitt, whose earliest attributable essay appeared on 18 February 1728 (source: Simon Targett, Oxford DNB). In Pitt’s dialogues, obviously inspired by Mandeville’s dialogues between Cleomenes and Horatio, the character of Philocles is “Shaftesburian”, and Horatio is Bolingbroke, of course, since Pitt was one of Robert Walpole’s leading political writers in The London Journal against Bolingbroke and The Craftsman.

• A separate defence of The Fable of the Bees.

As he refers to in The Preface of The Fable of the Bees, Part II , pp. 4-6, Mandeville delayed a defence of The Fable of the Bees. It seems possible that Mandeville’s Preface of The Origin of Honour and The Usefulness of Christianity in War was, partly or entirely, based on that non-published defence. The reasons for this assumption is that the character of this preface is quite unlike what might be expected, in view of this book’s contents. The preface does not deal with criticisms by Bolingbroke (‘Horatio’), but with criticisms on The Fable of the Bees made by others, such as William Law and Francis Hutcheson. So the preface might be considered as a (or the) separate defence of The Fable of the Bees.

• Epitaphium Mariae II.

A Latin epitaph by Bernard Mandeville, written in 1695, has recently been discovered by Mikko S. Tolonen. It is added to Mandeville’s Bibliography. Tolonen mentions this find in his dissertation 'Self-love and self-liking in the moral and political philosophy of Bernard Mandeville and David Hume' (Helsinki, 5 January, 2010). See also Tolonen’s Mandeville and Hume: anatomists of civil society (2013). The epitaph consists of four lines at the end, page 24, of An oration of Peter Francius, upon the funeral of the most august princess Mary II. Queen of Great Britain, France and Ireland (1695). Petrus Francius’s original funeral oration was in Latin. See Epitaphium Mariae II . Francius was a friend of Mandeville Latin School teacher Pieter Rabus.

• Mandeville’s Arminianism.

Understanding Mandeville demands not only a constant awareness of his being a physician, who is entirely devoted to preventing and curing psychosomatic disorders and diseases. A sound grasp of his Remonstrantism or Arminianism, as preceded by Coornhert and developed by Episcopius, Hugo Grotius, Philipp van Limborch and Jean Le Clerc, is necessary as well; see also Pieter Rabus. Mandeville is an outstanding exponent of this spiritual tradition of christianity, which embraces the notion of an ‘invisible church’ and is critical of the notion of the ‘visible church’, or, more enlarged, christendom. Therefore it is understandable that Mandeville is referring with approval to leading ‘Anglican Arminians’, such as bishop Jeremy Taylor (1613-1667) with his Discourse of the Liberty of Prophesying (1646) and archbishop John Tillotson (1630-1694) with his Rule of Faith , and also that Mandeville thinks himself as being looked upon [by supporters of the visible church] as a ‘Latitudinarian, if not worse’ ( Free Thoughts on Religion, the Church and National Happiness (ed. 1729), p. 82). See also the lemma ‘Arminianism’ by Ernestine van der Wall.

• Church of England.

In Free Thoughts Mandeville often refers to the Church of England as “our church” and claims to be (as ‘Loveright’, see The Mischiefs that ought to be apprehended from a Whig-Government , 1714, p. 27, juncto p. 17) one of its ‘Low Church’ members. This position of Mandeville’s has often been questioned. But rightly? Apart from the Arminian movement within this church, it should be considered what the Arminian professor Jean Le Clerc (1657-1736) states ‘concerning the question, what Christian church we ought to join our selves to’. Le Clerc states in Hugo Grotius’ The truth of the Christian religion (1711), p. 292: ‘It is therefore the part of a prudent Man not to enter himself into any Congregation (...), unless it be such in which he perceives That Doctrine Established, which he truly thinks to be the Christian Doctrine; so as that he is under no necessity of saying or doing any thing contrary to what he thinks delivered and commanded by Christ.’ So there are several Arminianisms (Dutch, Anglican), and personally Mandeville, who preferred episcopal church government to presbyterian church government, did not lack elbowroom in the Church of England.

• The New Testament only.

Jean Le Clerc adds (in Hugo Grotius’ The truth of the Christian religion (1711), p. 305) that ‘Nothing else ought to be imposed upon Christians, but which they can gather from the New Testament’. ‘If any thing further be required of them as necessary, it is without any Authority’. Mandeville’s view is identical; see e.g. An Enquiry into the Origin of Honour and the Usefulness of Christianity in War (1732), The Preface, first sentence, and the very last paragraph of these dialogues, p. 240. Note also Mandeville’s passage in Free Thoughts (1729, p. 161): ‘What sect or persuasion of christians has a better gospel to preach, or a more disinterested, and well meaning principle to walk by, than what the church of Rome had her origin from?’

• Mandeville not a deist.

So Mandeville is not a deist, as some authors assert, among whom Jonathan Israel in Radical Enlightenment . Mandeville is opposed to spinozism, which he relates to atheism and superstition for having all the same origin, as explained in The Fable of the Bees, Part II , p. 312. (In Mensen spreken niet om begrepen te worden (2007), p. 296-7, plus note.) The gap between Mandeville and Spinoza does not seem to be smaller than the one Bonger found between Coornhert and Spinoza: ‘a huge, unbridgeable gap’. (see H. Bonger, Spinoza en Coornhert (1988), p. 16.) On the gap between Spinoza and Arminianism, see also the lemma ‘Arminianism’ by Ernestine van der Wall (1-jan-2008) in the Oxford Encyclopedia of Enlightenment.

• Lieuwe van Aitzema .

In Free Thoughts (1720, p. 48; 1729, p. 53), Mandeville refers to the Dutch diplomat and historian Lieuwe van Aitzema (1600-1669), Herstelde Leeuw, of Discours over ‘t gepasseerde in de Vereenighde Nederlanden in ’t Jaar 1650 ende 1651 (1652). Its English translation: Notable Revolutions, beeing a True Relation of what hap’ned in the United Provinces of the Netherlands in the years MDCL and MDCLI (1653). An amusing story of William’s baptism on 15 January, 1650, is on pp. 415-18, in the English version pp. 366-69. As for Mandeville’s note, read ‘Leiden’, instead of ‘Haarlem’.

• Mandeville to Music.

Daniel Swenberg, The Grumbling Hive, or How Vice is a Virtue and Vice Versa (2010). A new Ballad Opera, based on Bernard Mandeville’s (1670-1733) Fable of the Bees (1714) with music by his contemporaries and traditional Broadside Ballads.

• John Mackinnon Robertson .

Robertson’s essay on Mandeville. This essay in Pioneer Humanists (1907), ‘among the best analyses of Mandeville’ according to F.B. Kaye, Fable ii, p. 445, is not the same essay which appeared in 1886 and 1889, as stated by Kaye. The 1907 version, being revised and expanded by Robertson, is almost double the size of the 1889 version.

• William King , Thomas Burnet , and Charles Blount.

In his poem Typhon (1704), Bernard Mandeville writes (l. 6-10): ‘Or him that lost a Rib a sleeping,/ And dies for tasting of a Pippin;/ His Dame, or any one of those/ Which B----t has burlesqu’d in Prose.’ The source of these lines seems to be the ballad The Battle Royal by William King (1663-1712), stanzas IV and VI. In the last line, ‘B----t’ stands for Thomas Burnet (c. 1635-1715); the prose-work in question is Burnet’s Archæologiæ Philosophicæ or the Philosophical Principles of Things (1729, orig. in Latin 1692). The notion that Burnet burlesqued can be found in A Letter to my Worthy Friend mr Gildon in vindication of Dr. Burnet (1693), in Charles Blount, The Oracles of Reason (1693), in which Blount (1654-1693) states (p. 2): “Nor can I find anything worthy an objection against him [Burnet], as some of the censorious part of the world pretend; who would have you believe it a meer burlesque upon Moses.” Mandeville’s (‘Cleomenes’) criticism of Burnet, and his supporters, is in The Fable of the Bees, Part II (1729), ed. Kaye, p. 317-8.

• Aldhelm not to be imitated.

In Free Thoughts (ed. 1720, p. 196; ed. 1729, p. 217) Mandeville refers in a footnote to ‘History of the Works of the Learned for the Month of April, 1689’. In fact, he means Henri Basnage, Histoire des Ouvrages des Savans (Rotterdam, 1689), p. 164-5, in his review of Acta Sanctorum Maji (1688) by the Jesuits and Bollandists Godfried Henschenius and Daniel Papebrochius. The opinion of Aldhelme as being ‘an example rather to be admired than to be imitated’, quoted by Mandeville, is by Henschenius.

• Abraham van Kerckraed.

In A Treatise of Hypochondriack and Hysterick Passions (1711, p. 121) or - Diseases (1730, p. 132), Mandeville refers to a promotion of a doctor in the Civil Law at Utrecht, whose thesis was de Codicillis . The only person to be considered for having been this candidate is Abraham van Kerckraed (Abrahamus à Kerkraad), abt. 1665-1715, defending his Disputatio juridica de codicillis at Utrecht in the year 1686.

• Joost van den Vondel.

A short article on, most likely, the original kernel of Mandeville’s Grumbling Hive or Knaves turn’d Honest ( 1705): ‘Iupiter en de Honich Bije’ (‘Jupiter and the honeybee’), by the renowned Dutch poet and playwright Joost van den Vondel (1587-1679). See Research.

• Petrus Rabus.

On the track of Pieter Rabus (1660-1702), Mandeville’s teacher of literature, and fables. Aesopian fables as required teaching material Greek language, and implying a course ‘human nature’ at the Latin School. Added: ‘A Summary in English’, which may be considered as a description of the Rotterdam cultural nursery in which Mandeville was educated. See Research.

• Jean-François Sarasin .

‘When Adam saw the beauty by his side’, the verses read out by Antonia in The Virgin unmask’d (1709), pp. 129-130), are an imitation of Jean-François Sarasin's (1614-1654) famous Sonnet à Monsieur de Charleval , ‘Lors qu’Adam vit cette jeune beauté’, found in Sarasin's Poésies (1658), p. 61. Mandeville most likely found the reference to this sonnet in Bayle’s Dictionaire, art. ‘Eve’, 2:422. He must also have liked Sarasin’s almost equally famous ‘Ode sur la coqueterie’, ‘Mon cher Thyrsis, dequoy s’étonnes-tu, De voir Cloris Coquette & coqueteé’. In his appreciation of Sarasin’s so-called ‘Eve sonnet’, Mandeville differs from Bayle.

• Bussy-Rabutin .

The same page in Bayle’s Dictionaire , 2:422, contains also Roger de Bussy-Rabutin’s (1618-1693) poem ‘Je penserois n’être pas malheureux’. This is from his story on Mme d’Olonne and her husband making love, in Histoire amoureuse des Gaules, p. 224. The story may, in a contrary way, have inspired Mandeville when writing his poem 'Leander’s excuse to Cloris', in Wishes to a Godson (1712).

• William Cowper alias Volpone .

Of Mandeville’s poem 'Leander’s excuse to Cloris', in Wishes to a Godson (1712) appeared an earlier version The Libertine to his Platonic Wife in The Female Tatler, 28 till 31 October 1709, a contribution probably written by Mrs. Crackenthorpe (Mary Delariviere Manley). The libertine is William Cowper (1666-1709) alias Volpone; see Delariviere Manley (1663-1724), Secret Memoirs and Manners of Several Persons of Quality, of Both Sexes. From the New Atalantis, an Island in the Mediteranean (1709), pp. 213-7.

• Stafford’s corrigenda to Private Vices Publick Benefits?

– The Contemporary Reception of Bernard Mandeville edited by J. Martin Stafford (Solihull: Ismeron, 1997) ISBN 0951259458: click www. ismeron.co.uk.

• Michel Onfray.

Onfray’s play (2012) La sagesse des abeilles, (‘The wisdom of the bees’) is reminiscent of Fénélon’s (1651-1715) fable Les Abeilles (‘The bees’). The nietzschean idealist Onfray (1959) considers Bernard Mandeville to be a ‘piètre moraliste’ (‘paltry moralist’). But Mandeville is no moralist. As a psychiatrist, he is telling what people really are, not what they should be. ( The Fable of the Bees , ‘An Enquiry into the Origin of Moral Virtue’, The Introduction.)

• William Brown Galloway .

Galloway (1811-1903) conducted Moral Philosophy Class in Glasgow University during portion of Session 1836-37. Not much attention, if any, has been paid to his account of Mandeville’s views in his book Philosophy and religion, with their mutual bearings comprehensively considered, and satisfactorily determined, on clear and scientific principles (1837), pp. 357-366, and pp. 524-544. See Galloway on Bernard Mandeville, and Adam Smith, via page Selectie van artikelen over Mandeville.

• William Deresiewicz.

Fables of Wealth (2012), An essay on the morality of capitalism (or lack thereof), from the May 13, 2012, edition of the New York Times Sunday Review.

• John Hawkesworth.

Hawkesworth (1719-1773) referred to Bernard Mandeville, in his article ‘The Character of a Gamester defended’, published in his London newspaper The Adventurer of 13 February 1753. A Dutch translation appeared in De Philantrope, of 9 March 1757. Hawkesworth’s reference is not in Kaye’s list of ‘References to Mandeville’s Work’ (Fable ii, p. 418). Via page Selectie van artikelen over Mandeville.

• Conor P. Williams.

Bernard Mandeville's Defense of Imperfection and Human Flourishing (2010). Western Political Science Association 2010 Annual Meeting Paper. ‘I argue that Mandeville avoids reifying markets or laissez-faire economics as optimal or perfect, but instead treats them as frameworks within which individuals confront minimal uncertainty with a means to make failure valuable. It may be argued that this is only a matter of degrees of emphasis, that Smith, Hayek, and other free market supporters understood markets in much the same way as Mandeville. It is not my aim in this paper to trace the history of this particular conception of the market, but to argue that by taking Mandeville’s account as a model for our own arguments, we can better defend (and qualify) the value of free markets.’

• Quoting and quoting correctly .

See the article John Wesley versus Robert Sandeman, Mandeville among ranking preachers in 1756-7. And about Tomas Sedlacek (2011) and F.B. Kaye (1924), and the problem of quoting from quoting from quoting out of context.

• Thomas Babington Macaulay (1800-1859).

By placing him on Shakespeare’s level, Macaulay, in his ‘Essay on Milton’ (1825), was probably the first man to recognize Mandeville as a genius of science. See article.

• Messenger Monsey (1693-1788).

Resident physician of Chelsea Hospital, Mandeville’s Fable of the Bees he often read; and Jeremiah Whitaker Newman (1759-1839) did as well. See article.

• Bentley’s Monthly Review, or Literary Argus (1854).

Some passages of the article Mandeville’s “Fable of the Bees”, followed by Charles Caleb Colton. See article.

• George Lillie Craik (1798-1866).

‘Mandeville’ in Sketches of the History of Literature and Learning in England, with specimens of the principal writers (vol. v, 1845). See article.

• Johann Philipp Glock (1849-1925), Bernard de Mandeville’s Bienenfabel (1891). See article.

• Sylvie Kleiman-Lafon.

Mandeville’s Treatise of the Hypocondriack and Hysterick Passions and/or Diseases translated into French. Introduced, translated and annotated by Sylvie Kleiman-Lafon, under the title: Un traité sur les passions hypocondriaques et hysteriques (2012). The title is that of Mandeville’s 1711 edition, called A Treatise of the Hypochondriack and Hysterick Passions , but the translation includes all the additions of A Treatise of the Hypochondriack and Hysterick Diseases (1730), which appear in between brackets in the body of the text.

• Marina Bianchi.

In her 1993 article How to learn sociality: true and false solutions to Mandeville’s problem Marina Bianchi shows Mandeville to be a fruitful and future-proof basis for studying the reality of creative and dynamic economics, beyond e.g. Smith and Hayek. The so-called “Mandeville’s problem” is not a problem to Mandeville, but the problem of so many economists overlooking or abstracting from human nature as it is. See article, page Selectie van artikelen.

• Troppaniger, not Ettmüller.

In his Treatise of the Hypochondriack and Hysterick Diseases (1730), Mandeville states (p. 216) to be quoting Etmuller. But both this quotation and the German name ‘Der Gelahrten Kranckheydt’ , the disease of the learned , (p. 106) come from Johannes Christoph Troppanniger (1650-1729), i.e. from his medical dissertation De Malo Hypochondriaco (1676). Michael Ettmüller being Troppanniger’s supervising professor, this dissertation has been inserted in Ettmüller’s Opera Omnia.

• Neil de Marchi.

‘Serious misreadings of Mandeville are nothing new, but here as in certain other instances I would argue that attending to his medical views might have prevented some missteps.’ This remark (p. 88) in De Marchi’s very fine study ‘Exposure to strangers and superfluities, Mandeville’s regimen for great wealth and foreign treasure’ (pp. 67-92), in Peter Groenewegen (ed.) Physicians and Political Economy , six studies of the work of doctor-economists (2001), should be given due consideration to. Unfortunately, De Marchi did not deal with De Medicina Oratio Scholastica (1685), in which Mandeville explains his full outlook on medicine. By focussing on the cure of diseases, De Marchi misses the other, and more relevant half of Mandeville’s medical view, viz. the preservation of health and prevention of diseases.

• Johan van Beverwijck (1594-1647).

Mandeville’s Oratio on Medicine (1685) begins with the line: “Sallust rightly said, 'All our power lies in both the mind and the body'. Mandeville’s source is most likely one of the best known works by doctor Johan van Beverwijck, called Schat van Gesontheyt, ‘Treasure of Health’. Van Beverwijck (also Van Beverwyck and Beverovicius), in his explanation on pertubations in general, fol. 21-73, translated Sallust’s line into Dutch, p. 21. Like many Dutch families, the Mandevilles, father and son, grew up with Van Beverwijck’s handbook for health. At the core of Bernard Mandeville’s pre-academic development as a physician-to-be is dr Van Beverwijck. And via his (Joh. Beverovicij) Medicinae Encomium (1644) Mandeville came to read Erasmus’ Declamatio in Laudem Artis Medicae (English translation: The Prayse of Phisyke), to which references can also be found in Mandeville’s Oratio. As for an introduction to Van Beverwijck, see Cornelia Niekus Moore, Not by Nature but by Custom: Johan van Beverwijck's Van de wtnementheyt des vrouwelicken Geslachts, in The Sixteenth Century Journal, Vol. 25, No. 3 (Autumn, 1994), pp. 633-651. She is dealing with Van Beverwijck’s book ‘Of the excellence of the female gender’.

• Mandeville’s ‘feminism’ .

Mandeville’s opinion on women or the female gender as expressed in Virgin Unmask’d , his contributions to The Female Tatler and scattered throughout his other works, is in line with Van Beverwyck’s, whose argument in favour of women was opposed by most people (men?) in the Dutch Republic, including Cats, Huygens and the Calvinists. Van Beverwyck has been called a hyper-feminist, and Mandeville a proto-feminist. But in terms of Hippocratic medicine, the ‘feminism’ of these physicians is essentially a matter of health, in favour of half of the population.

• Hippocratic unity.

Mandeville, inspired by ‘the Divine Hippocrates, that prodigious Man (Treatise of the Hypochondriack and Hysterick Diseases, 1730, p. 38),’ breathes Hippocratic medicine. Mandeville’s entire oeuvre shows an admirable ‘Hippocratic unity’ with respect to approach, content and objectives.

• Hayek, Mandeville and Hippocrates.

In spite of Mandeville’s explanation in A Treatise of the Hypondriack and Hysterick Diseases (1730), pp. 33-41, Friedrich A. von Hayek overlooked the Hippocratic heritage that Mandeville himself was fully aware of. Hayek’s idea of a creative, spontaneous order looks like a specimen of Hippocratic thought. Hayek’s reference to the Hippocratic oath, in his speech at the Nobel Banquet (1974), may be significant in this respect. Hayek en Mandeville have Hippocrates in common.

• ‘The Moral’ of The Grumbling Hive or Knaves turn’d Honest (1705).

As to contents, Mandeville’s famous ‘Moral’ is essentially based upon the views expressed in Johan van Beverwijck, Schat der gesontheyt (1636), dl. i, ‘Van de bewegingen des Gemoedts in ’t gemeen’. (‘Of the mind’s pertubations in general’). See the article Johan van Beverwijck en Mandeville, in which attention is drawn to ‘lopt and bound’; to Van Beverwijck’s conclusion of ‘going backwards, and destroying everything’, if the heart becomes unmovable; and to the acorns, as mentioned and meant in the last line of The Grumbling Hive, have also been derived from Van Beverwijck, Schat der gesontheyt (ed. 1643), pp. 339-42. Van Beverwijck’s lemma on acorns starts like this: ‘Acorns are not only looked upon by almost all heathen authors as being the oldest fruits, but also the only food on which alone the first world used to live.’

• Otto Bobertag (1879-1934).

In 1914 Bobertag published Mandevilles Bienenfabel , a German edition of The Fable of the Bees. In 1918 he wrote an article on Mandeville as a psychologist of warfare, 200 years ago: Ein Kriegspsychologe vor 200 Jahren.

• Montaigne.

Mandeville’s definition of ‘Virtue’, derived from Montaigne. See Research items.

• Mario Relich.

A fine and valuable investigation of Mandeville’s dialogues by Mario Relich, up to now apparently unnoticed in Mandevillean literature: The Technique of Philosophical Dialogue in the Works of Mandeville, Shaftesbury and Berkeley (1976), pp. 39-244; 359-75. In Relich’s opinion, Mandeville’s “use of paradox, in contrast [with Berkeley], is highly open-ended (…); [he] seems more interested in inducing the reader to think in a certain manner rather than merely accept certain doctrines.” (pp. 226-7). This may be expected from Mandeville, being a pioneer psychiatrist, and inventor of the modern or humanistic method of talking therapy, rediscovered or re-invented in the 20th century. Mandeville claimed his invention in A Treatise of the Hypondriack and Hysterick Passions (1711), p. xiii: “If a Regular Physician writing of a Distemper, the Cure of which he particularly professes, after a manner never attempted yet, be a Quack (…), then I am one.”

• Mandeville’s idiosyncrasy.

Mandeville’s so-called individualism is a matter of idiosyncrasy, which is basically Hippocratic. In Hippocratic medicine, each person is different. What person the disease has, is far more important than what disease the person has. Mario Relich (o.c. p. 123) concludes: “Philopirio's [Mandeville’s] "method" (…) is highly flexible and geared to the treatment of individual cases, while the "rationalist method" treats diseases on a more generalized level, abstracted from the individual patient. (…) Such an interlocutor as Misomedon is not only a "typical" case of hypochondriasis but an individual whom hypochondria affects in a combination of ways bound to be different from its effect on any one other patient.” As for Mandeville’s approach, see A Treatise of the Hypondriack and Hysterick Passions (1711), pp. 258/9; in A Treatise of the Hypondriack and Hysterick Diseases (1730), pp. 343-5, 377-8.

• To his Royal Majesty William III.

Irwin Primer came across an entry of a pamphlet by Bernard Mandeville, held by the University Library of Leiden. The poem, dating from 1691 and consisting of 20 lines, is called Aan sijn koninklijke majesteyt Willem de III. koning van Groot Brittanje, &c. &c. &c. ter selver overkomst uyt Engelant in Hollant ; that is ‘To his Royal Majesty William the Third, King of Great Britain, &c., &c., &c. for his arrival in Holland from England’. See page Mandeville's oeuvre per publicatie .

• A second German edition of The Fable, Part II.

The German translation of The Fable, Part II , called Anti-Shaftsbury oder die entlarvte Eitelkeit der Selbstliebe und Ruhmsucht, in philosophischen Gesprächen, nach dem Englischen , was published in 1761. A second version in 1766, so far hardly noticed, got a different title: Gedanken des Englischen Weltweisen über die Thorheiten des Menschen , [Thoughts of the English worldly-wise man on the human follies] in Gesprächen, nach der neuesten Englischen Ausgabe mit Anmerkungen übersetzt.

• Harold J. Cook: Matters of a Hypothetical Doctor. See Research items.

• 300th Anniversary of The Fable of the Bees .

Irwin Primer made a useful report about the recent conferences on Mandeville, with a list of all of the speakers and papers presented between 2011 and 2014. Go to this website:http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.7282/T3222T1J . See also the lecture 'Bernard Mandeville in vier kenmerken' (Bernard Mandeville described in four special features).

• Ernest Seillière.

Seillière (1866-1955), not mentioned by F.B. Kay in his 'References to Mandeville's work', pays substantial attention to Mandeville in his L’ impérialisme démocratique (1907), 'Bernard Mandeville et la morale impérialiste', pp. 62-130, and 'Bourgades et Capitales. Mandeville et Rousseau', pp. 165-181. German translation: Der demokratische Imperialismus (1907).

• Robert Michels (1876-1936)

Michels writes in his 'Beitrag zur Kritik einer eudämonistischen Oekonomik', in Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft, Festschrift für Franz Oppenheimer (1924) , p. 113: 'Die Dynamis des Verlangens nach Macht, des Machtsinstinktes, darf nicht verkannt werden. Mandeville hat ihm als instinct of sovereignty and of self-liking die zentrale Stelle der menschlichen Psychologie überhaupt zugeschrieben. Neuerdings haben Sexualforscher selbst den Geschlechtstrieb auf den Machtsinstinkt zurückgeführt'. [The dynamis of the desire for power, of the instinct of power, must not be misjudged. To it, as instinct of sovereignty and of self-liking, Mandeville has acribed the central place of human psychology at all. Recently sexuologists have even led the sexual drive to the instinct of power.] In a footnote Michels refers to The Fable of the Bees , but 'instinct of sovereignty and of self-liking', as quoted by Michels, is not be found in this work. The sentence 'It is self-evident, that they point at self-liking and the instinct of sovereignty' is in Mandeville's Enquiry Into the Origin of Honour, and the Usefulness of Christianity in War , p. 68-9. Robert Michels' source may have been Ernest Seillière's tentative understanding of the relationship between self-liking and the instinct of sovereignty in L’ impérialisme démocratique (1907), p. 78; Der demokratische Imperialismus (1907), pp. 63).

• Alfred Adler (1870-1937).

Concerning the 'Geschlechtstrieb' [sexual drive] Robert Michels (see before) adds a footnote: 'Ueber die versteckte Art Machtscharakter bei weiblicher Neurose und Exhibitionismus, vgl. Alfred Adler, Ueber den nervösen Charakter (1912), p. 106.' From this Oliver Brachfeld (1908-1967) concludes in his Inferiority feelings in the individual and the group (1951), p. 43-4, that Robert Michels considered Mandeville to be a fore-runner of the Austrian psychologist and psychiatrist Alfred Adler (1870-1937). It should be noted, however, that Adler's views are based on an idealistic and moralistic approach of human life, that Mandeville fundamentally disapproves .

• Hans Vaihinger (1852-1933).

'Adam Smith‘s nationalökonomische Methode', in Die Philosophie des Als Ob , p. 353 (in The Philosophy of 'As If' (1911), p. 187) : Diese Methode ist nach Oncken [Aug. Oncken, Adam Smith und Immanuel Kant (1877)] eine kennzeichnende Eigentümlichkeit von Smith. Es handelt sich, sagt eben derselbe, bei der ganzen Frage um nichts Anderes, als um das Wesen der rationalen Forschungsmethode überhaupt, deren charakteristische Eigentümlichkeit es ist, die Dinge in der Einbildung von allen äusseren Einflüssen zu trennen, um sie ganz isoliert mit Rücksicht auf einen besonderen Zweck zu betrachten. Es ist, fügt derselbe richtig hinzu, die Methode, welche durch Cartesius für die Untersuchung einzelner Objekte in die Wissenschaft eingeführt, durch Kant und Smith aber auf ganze Abteilungen der Philosophie ausgedehnt worden ist. Er hätte noch hinzufügen können,dass diese Methode im 18. Jahrhundert viel gebraucht war, und dass im Laufe der Zeit und besonders im 19. Jahrhundert nach dem „Gesetz der Ideenverschiebung" aus Fiktionen der Meister Dogmen der Schüler geworden sind. [and that in the course of time, particularly in the 19th century, through the operation of the "law of ideational shift", the fictions of the masters developed into the dogmas of their followers . italics ACJ] *) Hans Vaihinger's footnote: 'Die Smith'sche Methode hängt mit den im 18. Jahrh. beliebten Fabeln und Utopien zusammen, u. A. besonders mit der Mandeville'schen Bienenfabel , wie Karl Marx ( Das Kapital I , S-339, Anm. 57) bemerkt.' [Karl Marx, Das Kapital I (1867), S-339, Anm. 57: … Der berühmte Passus in demselben (A. Smith: Wealth of Nations , b. I, ch. I.) Kapitel, der mit den Worten beginnt: “Observe the accomodation of the most common artificer or day labourer in a civilized and thriving country etc. " - und dann weiter ausmalt, wie zahllos mannigfaltige Gewerbe zur Befriedigung der Bedürfnisse eines gewöhnlichen Arbeiters zusammenwirken, ist ziemlich wörtlich kopirt aus B. de Mandeville's 'Remarks' zu seiner The Fable of the Bees, or Private Vices, Publick Benefits .] Another reference to Mandeville is in Hans Vaihinger, Die Philosophie in der Staatsprüfung (1906), p. 173.

• Jules Delvaille (1862-1915/16?).

Essai sur l'histoire de l'idée du progrès jusqu'à la fin du XVIIIe siècle (1910), dealing with Bernard Mandeville, pp. 431-442.

•

Jean Le Clerc

(1657-1736).

Mandeville is not very sparing with the term ‘learned man’. What ‘a learned man’ says in Free Thoughts (ed. 1720, p. 41; ed. 1729, p. 44) is by Jean Le Clerc, the influential Remonstrant or Arminian professor in Amsterdam, in The Lives of the Primitive Fathers, viz. Clemens Alexandrinus, Eusebius, Bishop of Cæsarea, Gregory Nazianzen, and Prudentius, the Christian Poet (1701), p. 317.

• Jean Le Clerc's Parrhasiana.

A most relevant missing link in Mandeville-studies. Le Clerc's Parrhasiana, ou Pensées diverses sur des matières de critique, d'histoire, de morale et de politique (Amsterdam, 1699) and Parrhasiana etc., Tome Second (Amsterdam, 1701) appear to have been an important source for many of Mandeville's items and views as expressed in The Fable of the Bees, in The Mischiefs That Ought Justly to Be Apprehended from a Whig-Government (1714), and in Free Thoughts on Religion, the Church and National Happiness (1720). The Dutch translation (1703, reissued 1715) includes both parts of Parrhasiana ; the English translation (1700) contains only the first part. See the next point.

• Free Thoughts: 'Mandeville's Parrhasiana'.

As to title and contents, Mandeville's Free Thoughts on Religion, the Church and National Happines is reflecting Le Clerc's Parrhasiana to a considerable extent. 'Parrhasiana' - compare 'parrhesia'- are not simply 'pensées, thoughts', but 'free thoughts'. 'Religion', 'Church' and 'National Happiness' form a substantial part of, in particular, the second part (1701) of Le Clerc's Parrhasiana ; which already stands at reading through its index. See recent article, page Research items.

•

A reference to Mandeville in 1709.

The earliest reference to Mandeville, mentioned by F.B. Kay in his 'References to Mandeville's work', dates from 1716. But Virgin Unmask'd (1709) was in 1709 referred to as a book being "admired" and "in vogue". Mandeville is said to belong to "the authors that now treat about Love, and consequently would raise that Passion in others; the more vicious their Design is, the more modest and courtly shall be their Expressions." The book "puts poys'nous Love upon us, under pretence of giving us an Antidote against the Passion", according to the anonymous author, "A physician in the country", in An Apology for a Latin Verse in Commendation of Mr. Marten's [see John Marten] Gonosologium novum; or appendix to his sixth edition of The venereal disease: Proving That the same Liberty of Describing the Infirmities and Diseases of the Secret Parts of both Sexes, and their Cure, (which in his Appendix is said by s ome to be Obscene) has been all along us'd both by Ancient and Modern Authors, in their Physical and Chirurgical Discourses (1709), pp. 44-5.

• Sebastian Bretschneider.

A new and interesting approach of Mandeville's political thought, inspired by Volker Gerhardt's (*1944) philosophical ideas, is presented in a recent dissertation (2013) by Sebastian Bretschneider. The thesis, in German, with an abstract in English, is called Die Anatomie der Ordnung, zum politische Denkens Bernard Mandevilles ('The anatomy of order, on Bernard Mandeville's political thought'). It is available on the internet; see 'Volltext'.

• A Dutch 'Society of Fine Ladies', Chavigny de la Bretonnière and Mandeville.

Basic findings: The Female Tatler by 'A Society of Ladies' was modeled on the lines of a Dutch novel called The present-day The Hague and Amsterdam's Fine Ladies, their Lives and Businesses , featuring a Dutch "Society of Fine Ladies". In it, 'Artesia' is the main character. Mandeville borrowed this name for his contributions to The Female Tatler. Mandeville's Virgin Unmask'd was modeled on the lines of Chavigny's Venus dans le cloître, ou la Religieuse en Chemise . Also added some other similarities between Mandeville and Chavigny's Venus dans le cloître , including the beginning of The Grumbling Hive's 'Moral'. And a suggestion that 'Antonia' in The Virgin Unmask'd was named after Pietro Aretino's Antonia in Ragionamento della Nanna et della Antonia (1534). See recent article. page Research items.

• Gassendi.

There is no evidence that Mandeville ever read a work by Gassendi or Gassendus. According to E.G. Hundert, Mandeville "he (Mandeville) declared himself to be Gassendi's disciple" in the 1730s editions of his Treatise on Hypochondriack and Hysterick Diseases . In a footnote, Hundert ( The Enlightenment's Fable (1994), p. 45) is referring to p. 21 of Mandeville's Treatise . However, Gassendi's name is not mentioned at all in Mandeville's Treatise . In Free Thoughts (1720), p. 177, footnote, Mandeville refers to 'Bernier's Abridgment of the Philosophy of Gassendus', but this is just a reference he took, like so many others, from Bayle's Dictionary , in casu lemma Mahomet . As stated further up, Mandeville mistakenly replaced Galileo Galilei by Gassendi in The Fable of the Bees, Part II . Mandeville did mention Gassendi only once. In his 1689 disputatio De Brutorum Operationibus , but there Mandeville is quoting from a textbook used in the foundation course at the Leiden university, namely Antonius Le Grand, H istoria naturae, book III, Dissertatio de carentia sensus et cognitionis in brutis . Mandevilles disputatio leans to a large extent on Le Grand's dissertation. Just like another 1689 disputatio, bearing the same title as Mandeville's, by a fellow-student, called Cornelius Hooimond (1668-1727). Hooimond became a parson.

• Mandeville building .

The tallest building of the Woudenstein campus of the Erasmus University at Rotterdam has been named after Bernard Mandeville. Search 'Mandeville Building' on Google. It is the first tangible recognition of Mandeville in the Dutch public domain. And perhaps in the whole world.

• Mandeville: On Johannes van den Heuvel.

In 1689, Bernard Mandeville wrote an occasional poem, In Joannis van den Heuvel , in Latin, dedicated to Johannes Van den Heuvel (1666-1718), and published in Van den Heuvel's Disputatio Juricica Inauguralis de Mutatonibus , Franeker (1689).

• Bruce Elmslie. Publick Stews and the genesis of public economics. 'Mandeville’s analysis of the problems in the market for sex (private and commercial) represents a relatively complete and early analysis of markets from the perspective of market and government failures.'

• Saul Ascher and Mandeville .

Exactly two hundred years ago: Saul Ascher (1767-1822) published his effort to have The Fable of the Bees of Mandeville meet contemporary German-philosophical demands. He called it: Bernhard von Mandeville's Fabel von den Bienen (1818). See the page ' Selectie van artikelen '. (Apart from this, Ascher's Die Germanomanie - Germanomania- (1815) should be taken notice of, in view of both the past and current ideologies of nationalism.)

• Mandeville's synonyms for

filautia : 'self-love' and 'self-liking'.

Mandeville's claim of having invented or coined the word 'selfliking', in the Erasmian sense he used it, is not right. Thomas Chaloner was ahead of him, in 1549, when he translated Erasmus' Stultitiae Laus or Moriae Encomium into English. He translated filautia as 'self-liking'; not as 'self-love'. Using the word 'self-love' (corresponding with 'eigenliefde' in Dutch), Mandeville's notion of it was Erasmian, and similar to Chaloner's . Seeing that the word 'love' ( i.e. fil- in filautia ) opened up (critical) misunderstanding, or as Mandeville said: 'since it has been in Disgrace' (Fable ii, p. 135), he solved a purely semantic problem by introducing self-'liking' ('liking' to be understood as predilection or preference). Usually, liking means a weakened form of loving, but in this case not to Mandeville, as can be learned from his explanation: 'That Self-love was given to all Animals, at least, the most perfect, for Self-Preservation, is not disputed; but as no Creature can love what it dislikes, it is necessary, moreover, that every one should have a real liking to its own Being, superior to what they have to any other. I am of Opinion, begging Pardon for the Novelty, that if this Liking was not always permanent, the Love, which all Creatures have for themselves, could not be so unalterable as we see it is.' Though adapting his wording, Mandeville's initial understanding of filautia remained the same.

As to the 'Disgrace' , Mandeville may have had Joseph Butler in mind, as F.B. Kaye suggests ( Fable ii, p. 129), but William Law and George Cheyne are more likely. Supposing that Mandeville did not see Chaloner's translation, he may have heard the term self-liking from John Strype (1643-1737), of Dutch descent (surname 'Van Strijp'), clergyman, historian and lecturer at Hackney, where he also lived, ‘yet very brisk and well,’ though turned of ninety in 1733.’ The word 'self-liking' occurs in context in a document (from 1573) in Strype's publication The life and acts of John Whitgift, the third and last Lord Archbishop of Canterbury (1718). Mandeville's view concerning the innate self-liking in animals has been confirmed by the Dutch primatologist and ethologist Frans de Waal (*1948); see Wikipedia.

• Ferdinand Ludwig von Hopffgarten

(10-7-1745-/-08-03-1806),

Versuch über den Charakter des Menschen und eines Volkes überhaupt

(1773). ('Essay on the nature of man and of a people in general.') In an interesting and well structured textbook (divided in two parts; 138 sections spread over 226 pages) Von Hopffgarten, an appeal lawyer and author in Dresden, consistently reflects the basics of Mandevillean natural and individual psychology as well as its cultural and political implications. Without mentioning any contemporary writer, like Bernard Mandeville or, for instance, Montesquieu. Not mentioned by F.B. Kaye. (His name also appears as Ludwig Ferdinand (von) Hopf(f)garten.)

• November 15, 2020. On this day, it was 350 years ago that Bernard Mandeville was born in Rotterdam. In order not to let this fact go completely unnoticed, we pay attention to the thesis of Rex Anthony Collins: Private Vices, Public Benefits; Dr Mandeville and the Body Politic (1988), since it was Collins's aim to rehabilitate or recover Mandeville-the-physician; which is absolutely necessary. The dissertation is a commendable achievement in demonstrating that Mandeville's approaches are similar in The Fable of the Bees and A Treatise of the Hypochondriack and Hysterick Diseases . From this finding, Collins could easily have concluded, that his starting point, namely the a priori distinction between Mandeville's medical and non-medical thought, eventually turned out to be untenable a posteriori , and that Mandeville-the-physician cannot be rehabilitated or recovered but by understanding that Mandeville was a specialized physician, now to be referred to as a psychiatrist. See for Collins also page Selectie van artikelen over Mandeville .

• Mandeville, the author, identifies himself as a physician in

The Fable of the Bees. Mandeville's commitment to his profession as a physician when writing

The Fable of the Bees (1714) is explicitly stated by himself in the Preface, p. 9 (ed. Kaye), when saying: 'I think myself oblig'd to shew, that it [the book] cannot be prejudicial to any; for what is published, if it does no good, ought at least to do no harm'. A clear statement in terms of the

Hippocratic Oath .

• The origin of The Fable of the Bees (1714): As a writer, Mandeville was rather responsive, but not always readily. Nine years passed by before his rhymed pamphlet The Grumbling Hive (1705) was reprinted. The reprint, extensively exemplified, became Mandeville’s third book of his own, The Fable of the Bees (1714). Why so late? Who or what triggered Mandeville? Article may be read via the page Research items.

2021-2022

• Charles de Rochefort (1604/05- 1683). De Rochefort, living at Rotterdam from 1653-1683, was a close friend of Michael de Mandeville and his family, including Bernard. De Rochefort wrote L'Histoire naturelle et morale des îles Antilles de l'Amerique (1658) - Dutch translation in 1662 - and Tableau de l'isle de Tabago ou de la Nouvelle Oüalchre (1665). He was most likely Bernard Mandeville's first anthropological source; from The Planter's Charity (1704) up to An Enquiry into the Origin of Honour, and the Usefulness of Christianity in War (1732). Recent article (June 2021) may be read via the page Research items.

• Michael de Mandeville.

Three notarial deeds in connection with Michael de Mandeville's death in 1699. Its transcripts by mr. René Willemsen may be read via the page

Biografie en genealogie.

• Pieter de la Court (1618-1685). During a very short period of time, Mandeville, acting as a fabulist, wrote 3 fables of his own, including The Grumbling Hive or Knaves turn'd Honest (1705). This last fable, his earlier fable 'The Carp', and the explanatory structure of the book The Fable of the Bees (1714) can be linked directly to Pieter de la Court's Sinryke Fabulen (1685); the Dutch original , not so much its English translation Fables, Political and Moral, with large Explanations (1703). See the page Research items, the articles Mandevilles episode als fabeldichter and The origin of The Fable of the Bees (1714).

• Irwin Primer (1929-2020). Just now, Sept. 05, 2021, read on the internet, a message from ASECS on Facebook, Dec. 4. 2020: 'We are grieved to report the passing on Tuesday, December 1, of Irwin Primer, a longtime member of ASECS. His son reported to the c18-l list that his father had been getting weaker throughout 2020 and died peacefully. Professor Primer, who was the author of "Bernard Mandeville’s A Modest Defence of Publick Stews: Prostitution and Its Discontents in Early Georgian England," was an emeritus professor of English at Rutgers University.'

• Renatus Willemsen, Bernard Mandeville, Een ondeugend denker? Published in June, 2022. First biography ever of Mandeville and his works in Dutch.

2023

• Etmullerus Abridg’d.

Taking into account the style and contents of the translator's Preface of Etmullerus Abridg’d (1699) and comparing this to Mandeville's professional dispute, his professional career development and his Treatise of the Hypochondriack and Hysterick Diseases, there is sufficient reason for ascribing the abridgement and translation of Michael Ettmüller’s Opera Omnia (its Amsterdam 1696 edition) to Bernard Mandeville. See article in Dutch.

• Bernard Mandeville, De ontmaskerde maagd & Dagverhalen van Lucinda en Artesia. Een duologie.

Published on November 16, 2023. Book (a duology) in Dutch of The Virgin Unmask'd and Mandeville's Contributions to 'The Female Tatler'. With an Introduction (here) by Arne C. Jansen. See the page De maagd ontmaskerd & Dagverhalen.

• 31 December 1923<---->2023. F.B. Kaye finished the 'Prefatory note' of his well-known 1924 edition of The Fable of the Bees on 31 December 1923. Making his readers believe, that the Dutchman Bernard Mandeville could be or should be identified with just this book, he was - according to our experience - right in stating (volume I, viii) 'that it is very easy to skip, but not so easy to supply an omission.'

2024

• Bernard Mandeville, Ik ben Filopirio, Eigen therapie bij hypochondrie.

Dutch translation of Mandeville's Treatise of Hypochondriack and Hysterick Diseases (1730). Published on February 12, 2024. See the page Ik ben Filopirio.

• Bernard Mandeville, Autobiographical in cognitive behavioral therapy.

Introduction of the Dutch translation of Mandeville's Treatise of Hypochondriack and Hysterick Diseases (1730). To be read in English by scrolling down to the last article on the page Artikelen over Mandeville.